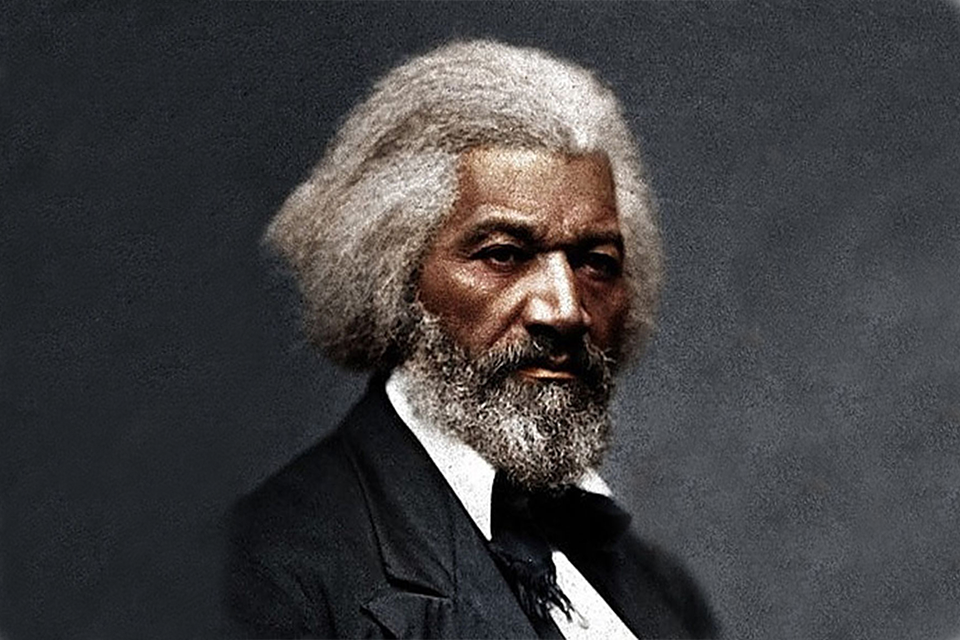

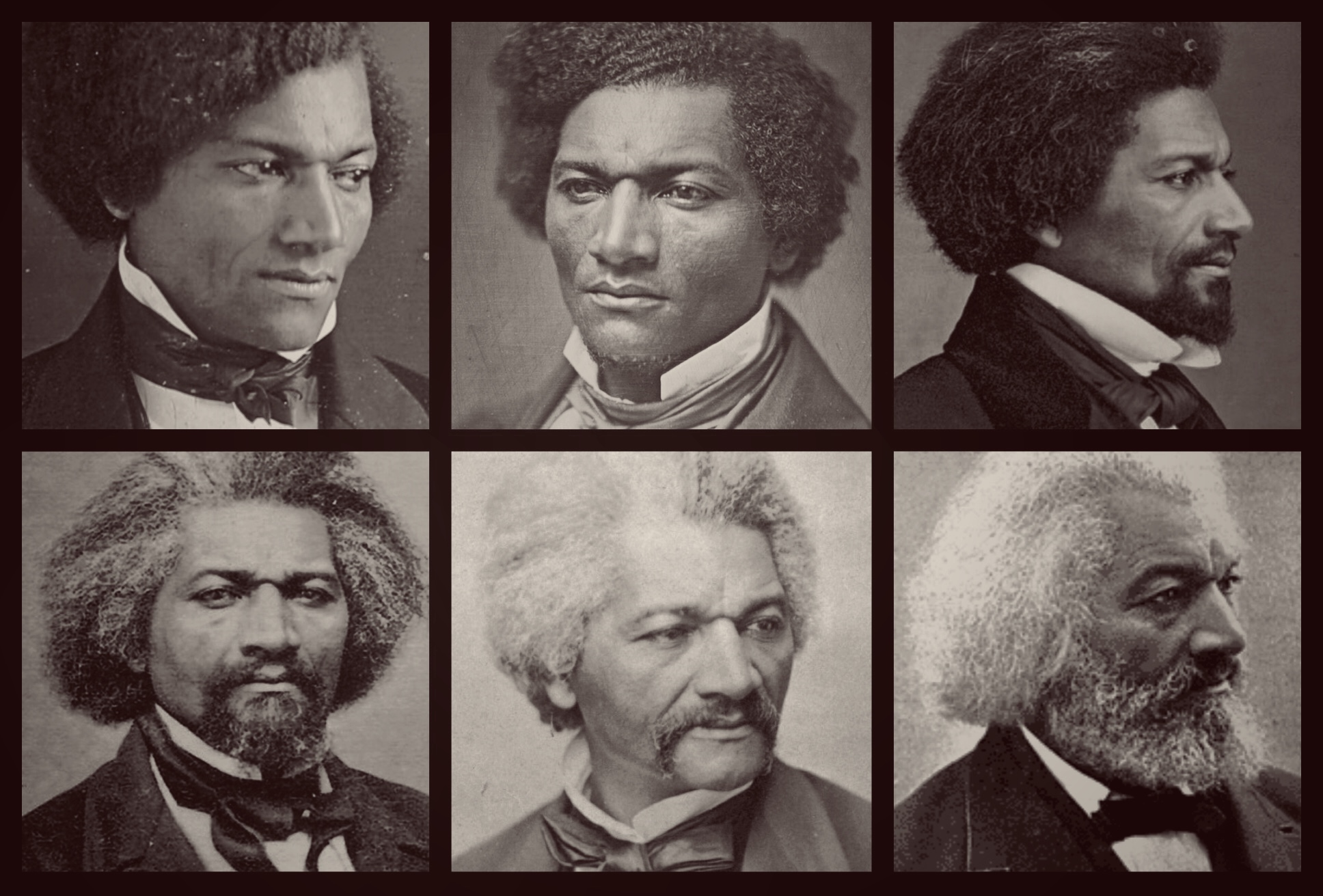

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass was born in a slave cabin, in February, 1818, near the town of Easton, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Separated from his mother when only a few weeks old he was raised by his grandparents. At about the age of six, his grandmother took him to the plantation of his master and left him there. Not being told by her that she was going to leave him, Douglass never recovered from the betrayal of the abandonment. When he was about eight he was sent to Baltimore to live as a houseboy with Hugh and Sophia Auld, relatives of his master. It was shortly after his arrival that his new mistress taught him the alphabet. When her husband forbade her to continue her instruction, because it was unlawful to teach slaves how to read, Frederick took it upon himself to learn. He made the neighborhood boys his teachers, by giving away his food in exchange for lessons in reading and writing. At about the age of twelve or thirteen Douglass purchased a copy of The Columbian Orator, a popular schoolbook of the time, which helped him to gain an understanding and appreciation of the power of the spoken and the written word, as two of the most effective means by which to bring about permanent, positive change.

Returning to the Eastern Shore, at approximately the age of fifteen, Douglass became a field hand, and experienced most of the horrifying conditions that plagued slaves during the 270 years of legalized slavery in America. But it was during this time that he had an encounter with the slavebreaker Edward Covey. Their fight ended in a draw, but the victory was Douglass', as his challenge to the slavebreaker restored his sense of self-worth. After an aborted escape attempt when he was about eighteen, he was sent back to Baltimore to live with the Auld family, and in early September, 1838, at the age of twenty, Douglass succeeded in escaping from slavery by impersonating a sailor.

He went first to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he and his new wife Anna Murray began to raise a family. Whenever he could he attended abolitionist meetings, and, in October, 1841, after attending an anti-slavery convention on Nantucket Island, Douglass became a lecturer for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society and a colleague of William Lloyd Garrison. This work led him into public speaking and writing. He published his own newspaper, The North Star, participated in the first women's rights convention at Seneca Falls, in 1848, and wrote three autobiographies. He was internationally recognized as an uncompromising abolitionist, indefatigable worker for justice and equal opportunity, and an unyielding defender of women's rights. He became a trusted advisor to Abraham Lincoln, United States Marshal for the District of Columbia, Recorder of Deeds for Washington, D.C., and Minister-General to the Republic of Haiti. Frederick Douglass died late in the afternoon or early evening, of Tuesday, 20 February 1895, at his home in Anacostia, Washington, DC."

Source: ~ http://frederickdouglass.org/douglass_bio.html

Selected Excerpts from

The Speeches/Writings

of Frederick Douglass

Farewell Speech to the British People

Delivered at London Tavern, London, England on March 30, 1847

- I do not go back to America to sit still, remain quiet, and enjoy ease and comfort. . . I glory in the conflict, that I may hereafter exult in the victory. I know that victory is certain. I go, turning my back upon the ease, comfort, and respectability which I might maintain even here. . . Still, I will go back, for the sake of my brethren. I go to suffer with them; to toil with them; to endure insult with them; to undergo outrage with them; to lift up my voice in their behalf; to speak and write in their vindication; and struggle in their ranks for the emancipation which shall yet be achieved.

West India Emancipation

Delivered in Canandaigua, New York, on August 3, 1857

- The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions yet made to her august claims, have been born of earnest struggle. The conflict has been exciting, agitating, all-absorbing, and for the time being, putting all other tumults to silence. It must do this or it does nothing. If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground, they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.

What A Black Man Wants

The speech before the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society at Boston.

This speech was printed in Equal Rights Pamphlets in April 1865.

- “The constitution of the human mind is such, that if it once disregards the conviction forced upon it by a revelation of truth, it requires the exercise of a higher power to produce the same conviction afterwards. The American people are now in tears. The Shenandoah has run blood~ the best blood of the North. All around Richmond, the blood of New England and of the North has been shed~ of your sons, your brothers and your fathers. We all feel, in the existence of this Rebellion, that judgments terrible, wide-spread, far-reaching, overwhelming, are abroad in the land; and we feel, in view of these judgments, just now, a disposition to learn righteousness. This is the hour. Our streets are in mourning, tears are falling at every fireside, and under the chastisement of this Rebellion we have almost come up to the point of conceding this great, this all-important right of suffrage. I fear that if we fail to do it now, if abolitionists fail to press it now, we may not see, for centuries to come, the same disposition that exists at this moment. Hence, I say, now is the time to press this right.”

"Untitled Speech" (popular title: "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" )

Delivered in Corinthian Hall, Rochester, New York, addressing the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society on on July 5, 1852

What, am I to argue that it is wrong to make men brutes, to rob them of their liberty, to work them without wages, to keep them ignorant of their relations to their fellow men, to beat them with sticks, to flay their flesh with the lash, to load their limbs with irons, to hunt them with dogs, to sell them at auction, to sunder their families, to knock out their teeth, to burn their flesh, to starve them into obedience and submission to their masters? Must I argue that a system thus marked with blood, and stained with pollution, is wrong? No! I will not. I have better employments for my time and strength than such arguments would imply.

What, then, remains to be argued? Is it that slavery is not divine; that God did not establish it; that our doctors of divinity are mistaken? There is blasphemy in the thought. That which is inhuman, cannot be divine! Who can reason on such a proposition? They that can, may; I cannot. The time for such argument is passed.

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation's ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy - a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.

Go where you may, search where you will, roam through all the monarchies and despotisms of the old world, travel through South America, search out every abuse, and when you have found the last, lay your facts by the side of the everyday practices of this nation, and you will say with me, that, for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival."

Self-Made Men

Delivered in 1859

"The pleasure we derive from any department of knowledge is largely due to the glimpse which it gives us of our own nature. We may travel far over land and sea, brave all climates, dare all dangers, endure all hardships, try all latitudes and longitudes; we may penetrate the earth, sound the ocean's depths and seep the hollow sky with our glasses, in the pursuit of other knowledge; we may contemplate the glorious landscape gemmed by forest, lake and river and dotted with peaceful homes and quiet herds; we may whirl away to the great cities, all aglow with life and enterprise; we may mingle with the imposing assemblages of wealth and power; we may visit the halls where Art works her miracles in music, speech and color, and where Science unbars the gates to higher planes of civilization; but no matter how radiant the colors, how enchanting the melody, how gorgeous and splendid the pageant: man himself, with eyes turned inward upon his own wondrous attributes and powers surpasses them all. A single human soul standing here upon the margin we call time, overlooking, in the vastness of its range, the solemn past which can neither be recalled nor remodelled, ever chafing against finite limitations, entangled with interminable contradictions, eagerly seeking to scan the invisible past and pierce the clouds and darkness of the ever mysterious future, has attractions for thought and study, more numerous and powerful than all other objects beneath the sky. To human thought and inquiry he is broader than all visible worlds, loftier than all heights and deeper than all depths. Were I called upon to point out the broadest and most permanent distinction between mankind and other animals, it would be this; their earnest desire for the fullest knowledge of human nature on all its many sides. The importance of this knowledge is immeasurable, and by no other is human life so affected and colored. Nothing can bring to man so much of happiness or so much of misery as man himself. Today he exalts himself to heaven by his virtues and achievements; to-morrow he smites with sadness and pain, by his crimes and follies. But whether exalted or debased, charitable or wicked; whether saint or villain, priest or prize fighter; if only he be great in his line, he is an unfailing source of interest, as one of a common brotherhood; for the best man finds in his breast the evidence of kinship with the worst, and the worst with the best. Confront us with either extreme and you will rivet our attention and fix us in earnest contemplation, for our chief desire is to know what there is in man and to know him at all extremes and ends and opposites, and for this knowledge, or the want of it, we will follow him from the gates of life to the gates of death, and beyond them."

The Church and Prejudice

Delivered at the Plymouth Church Anti-Slavery Society, November 4th 1841

"At New Bedford, where I live, there was a great revival of religion not long ago-many were converted and "received" as they said, "into the kingdom of heaven." But it seems, the kingdom of heaven is like a net; at least so it was according to the practice of these pious Christians; and when the net was drawn ashore, they had to set down and cull out the fish. Well, it happened now that some of the fish had rather black scales; so these were sorted out and packed by themselves. But among those who experienced religion at this time was a colored girl; she was baptised in the same water as the rest; so she thought she might sit at the Lord's table and partake of the same sacramental elements with the others. The deacon handed round the cup, and when he came to the black girl, he could not pass her, for there was the minister looking right at him, and as he was a kind of abolitionist, the deacon was rather afraid of giving him offence; so he handed the girl the cup, and she tasted. Now it so happened that next to her sat a young lady who had been converted at the same time, baptised in the same water, and put her trust in the same blessed Saviour; yet when the cup, containing the precious blood which had been shed for all, came to her, she rose in disdain, and walked out of the church. Such was the religion she had experienced!

Another young lady fell into a trance. When she awoke, she declared she had been to heaven. Her friends were all anxious to know what and whom she had seen there; so she told the whole story. But there was one good old lady whose curiosity went beyond that of all the others-and she inquired of the girl that had the vision, if she saw any black folks in heaven? After some hesitation, the reply was, "Oh! I didn't go into the kitchen!"

Quotes